tv U.S. Senate CSPAN November 13, 2012 9:00am-12:00pm EST

9:00 am

most like a, it is going to be a lot of attention focused on these leftover problems, which there was last year in the year before and the year before. and i remember when i, two years ago during the lame-duck win amid the do, when they struck a deal on the tax rates i just thought i'll now, this means we will be dealing with this right after the election. and the more you put that stuff off, you know, the more it piles up and just gets more and more difficult to deal with just the real again, nuts and bolts part of governing, which is getting the assistant secretary for labor and you know, the regional directors for epa and hhs in their jobs so that they can tell the politicals, on a political basis they can say like this is the direction we're taking him this is what the president has done. so it's a problem, you know. it's a potential ticket that

9:01 am

they are facing, but who knows? maybe they will give us an early christmas present at wrap up a lot of this business. >> i just remembered, chuck schumer and i think lamar alexander the pushed or are trying to push this bill through the senate that would reduce the number of appointees that the senate has to confirm. i don't know that the house will go along with it, but that could come back in the 113th spent on on that optimistic note, i think we are adjourned until after lunch. it's alcohol to your right, and we will reconvene down there a little bit. thank you. >> and live naturally form with a number of leading economist and political scholars on the economy, national security and so-called fiscal cliff. economists for peace and security and the new america foundation's economic growth program are hosting this panel discussion. this is expected to last to go to early this afternoon. this is live coverage on c-spa

9:02 am

c-span2. >> questions of military security, national security, economic security, social security, with the broad questions that we have all been grappling with four, intensely for the last four or five years. we are, strictly speaking, a professional organization. we are not an advocacy or lobbying group. we gather together, professionals working on these questions represent only themselves, and who had the advantage i believe of being able to speak to you with clarity and conviction. eps is also a membership organization. our website is www.eps

9:03 am

u.s.a..org. and i would invite all of you who are here and all who may be watching to visit the website. and if you share the goals and objectives of the organization to join us, or to lend us your support. we have a great advantage in privilege of having a very strong supporter and great friend in bernard schwartz, after whom this symposium is named. bernard planned to be here this morning, was not able to get here, but i do want to say that we at eps are tremendously appreciative of the bernard, of your encouragement and your backing over quite a long time

9:04 am

now, and though this symposium series. -- and other this symposium series. strip to essentials, the fiscal cliff is a device constructed in effect of course a rollback of social security, medicare, medicaid, among other programs. as the price of avoiding tax increases and disruptive cuts in federal civilian and in the military, it was partly fortuitous, given the expiration dates of the tax cut, but also partly policymaking by hostagetaking, timed for this moment following the 2012 elections, a contrived crisis,

9:05 am

the plane idea which is now unfolding was to force a stampede. in the nature of stampedes, arguments become confused, panic tends to flow, from fear compounded by doubt, especially when multiple, poorly understood forces, economic and political, all prepared to be pushing the same way. our task today is to sort through those forces, to ask whether any of them, taken singly or together, justify the voices of fear and doom that we are now hearing. i would like to break out this issue into, let's say four major questions. which, broadly speaking, frames

9:06 am

the structure of the morning's discussion. first of these is, is that really a looming debt and deficit crisis facing the government and the economy of the united states, in such a fashion that urgent action, major, involving major sacrifices is, in fact, needed now? there is obviously a very broad belief that this is the case. what is the foundation of that belief? and is without foundation sound? or is it possible that other issues should be considered more compelling and should be brought to the floor in this next period

9:07 am

of economic and political choices? secondly, knowing the question from the broader financial and fiscal position of the united states government, is there a crisis looming in the administration of financing come of social security, medicare, medicaid, which demands reform of those programs? or is this, again, a manifestation of a political agenda, not justified by concrete economic facts? that's the subject of the third panel. third, with the military sequestration, which is built

9:08 am

into the fiscal cliff, be the calamity that many have announced it to be? is it something that must be avoided by action within the next six weeks? that's the question which will be discussed in the second panel. and i believe that that panel will also take up the question of whether, even that we're 21 years after the end of the cold war, and that we have learned hard lessons in iraq and afghanistan, whether this is an inappropriate moment to begin to reconsider just what our national security posture and force structure should be. speaking for myself, i won't

9:09 am

prolong my opening remarks, i can give you my short answer to the three questions. is there a looming fiscal crisis for the united states government? now. no. are the compelling separate reasons to impose long-term cutbacks on social security, and specifically on medicare and medicaid, the federal component of our health care insurance system? no. do we face a disaster if we failed to act within the next six weeks, but instead defer decisions on all of these matters until the early part of next year? no. those are my short answers. my professional as well as personal message is, don't panic. this is not a moment of high drama. it's a moment for no drama.

9:10 am

the american people have expressed their confidence in the president, against a very clear alternative, who promised high rates of economic growth, a return to pass prosperity, at the price of and following very severe cutbacks in public functions and social insurance. the people expressed their disbelief in that formula. they did so i think very wisely. they also removed the argument, which i think was widely expected to hold, that we must act now because political conditions will be worse in january. and that this represents a kind

9:11 am

of last chance to get our house in order before entirely different political forces take control. not going to be true. the public insured that it won't be true. political conditions will be quite different in january from what was expected. personal view, they will be dramatically better. there is, in any event, at this moment space to think and consider what we should be doing, what our national priorities are, what a correct, sensible economic tells us about the balance of risks that we face, and we should use that space. and i suggest that this morning's symposium is really designed in that spirit, and i'm

9:12 am

very happy to be introducing it and to turn the podium over to stan collender who will moderate the first panel on the question of the fiscal cliff. >> thank you. i appreciate your returning the podium over to me but am going to sit here, if no one objects. in fact, we will all be sitting here. so just a word to the cameras that are following us. good morning, thank you. i often wonder what was going through an bernanke's mind when he used the phrase fiscal cliff for the first time. or when they decide that they couldn't say what they really wanted to say, which is that the combination of tax increases and spending cuts that will go to effect on january 1 and january 2 will go the deficit to far too fast. so, therefore, what he was really saying, cut the deficit to far too fast devastated economy and the fact the other elements contribute to gdp growth were unable to absorb it or offset it. so what are 90 was really saying

9:13 am

was he recommends the deficit be higher than it would otherwise be under current law. now, anyone who thinks that february 1 use the word fiscal cliff for the first time, when you first use the phrase, that he wants this document is that what you said? excuse us while we work this out. anyway, anyone who thinks the chairman of the fed could of got nothing february and still using the phrase fiscal cliff could have said i recommend congress increased the deficit is not reading the tea is quickly. back and figure and probably today, someone recommending that the deficit be higher, explicitly recommend the deficit-would be under current law would have that bull's-eye painted on his forehead a look of pride and a little bit bigger, and become more of a political target to if you will notice, all of the discussion about fiscal cliff so far, all those have been strongly recommending that it be avoided, limited, prevented, vindicated,

9:14 am

whatever, don't use the phrase and we think the deficit should be higher. two things, even though that is the inevitable conclusion, mathematically that is what has to happen. think of the letter that the 15 ceos from financial services companies released, i think is a publicly with a foot in the newspaper, to the 15 ceos from financial services companies to the president and congress about four weeks ago, in the sixth paragraphs in the letter they mentioned fiscal cliff seven times, never use the word deficit once. two weeks later, there was a letter from other sectors saying don't let the fiscal cliff happen, never mentioned the deficit once. so it's an interesting communications challenge that is, how do you say don't want the fiscal cliff to happen but you want spending to be higher and revenues to be lower? and, therefore, the deficit to be greater than it would otherwise be. that's one of several things were going to be discussing as a panel. i'm going to impose some rules here.

9:15 am

we are each one is going to be given five minutes or so on what we think are the key elements of the fiscal cliff, but you see the two microphones to i would like you to interrupt us as we go along but it will make it more fun, worthwhile and subsidy for everybody, especially for us out. if you just challenge us, ask more information, ask us to repeat something as we are going along. all we ask is -- do you have a question already? all we ask, i was thinking what could he possibly asking questions about? all the ask is you get to a microphone to do it. we are recording and that's the one thing you need to keep in mind, that he to get up in front of a microphone, your face will appear on c-span at some point. so with that in mind let me quickly introduce very, very briefly but then. stephanie kelton at the end. jamie you know, i'm not going to introduce him anymore other than to say that cheney. stephanie kelton is that the economics department at anniversary of missouri kansas city, right?

9:16 am

dedicate about? bruce bartlett is someone i've known forever. he used to block with me on my blog, thank you for asking, bruce. but is now one of the foremost authorities, has been for quite some time, on tax policy, tax reform. you can see him and his writings in "the new york times," the great economix blog. bruce also vice fiscal times, and he would be shooting me if i didn't mention the book, he's got several but the latest book is the benefits and burdens published by simon & schuster, casey and review related taxes were. i get my usual 10%. and chad stone is chief economist at the center for public policy. for those you don't know, the center, it is a place where budget analysts go to talk to budget analysts. they do just that pack your work. so stephanie, i'm going to start with you, all right? is a basic question, seems to be a look of shock in her face. basic question to start with.

9:17 am

janey said we shouldn't panic. but, you know, you cannot turn on cnbc or bloomberg and have them and your talk of people who are infected not to panic. if they're not over the top. economically speaking, is there a reason we should be concerned about the fiscal cliff? is so damaged that great, that vast that this has to be prevented under any circumstances? please use the microphone. >> no. i agree with jayme spent okay, we can move along. >> no, i think the clear and present danger is not, the deficit or the debt or the so-called fiscal cliff. it clear and present dangers really that we still have a very weak economy. and we are looking at, as you said, an environment in which people are really in panic mode over the fiscal cliff. and i think there is a lot of support actually because the

9:18 am

population doesn't seem to understand what exactly the fiscal cliff is and what it means and what they're hearing on television is an awful lot of hype about what's going to happen come if the fiscal cliff isn't a boy. and i think what that is doing is it's generating quite a bit of support for both sides to come together. it seems like the right thing to do, put your partisan differences aside and do what's best for the country. and figure out someway to avoid the cliff. and what that means in practice is striking some kind of a deal. what we are probably all heard referred to as a grand bargain. and i think what is important to keep in mind is that the grand bargain itself is really a form of austerity. it's an austerity plan. and so when you got an economy that is still struggling to fully find its feet, and you're at the same time talking about imposing austerity, i think we've seen pretty clearly watching what's been happening in europe the last three and a half or so years, but that's not a good idea.

9:19 am

we definitely have time to stop and get this right before we end up following greece than a terrible path. >> just to follow-up before we go to bruce, the congressional budget office says that gdp is going to fall by 2.9 percentage points if the fiscal cliff hits. first of all, can you explain, i don't think that happens on january 1, is that correct? >> the full effect certainly wouldn't happen. these are of course estimates about what might happen during the fiscal year. so sometime between january and september 30, yes, it is. you would see a sharp, a fairly sharp increase in unemployment and gdp growth actually turns negative so would result in a return to recession. >> but on january 3, it's not really like this is -- the center has talked about this as a fiscal slow, not a fiscal cliff. would you agree? >> right, because as these tax increases go into place, they don't going to place all at

9:20 am

once. you don't have billions of dollars on day one or day to rg3. the cats are the same way, right? spending cuts are phased in over a period of time. this is something that would work its way up over the course of many months to be something that can be fairly devastating for the economy. in a matter of days or weeks, no, you would get that kind of an outcome spent bruce can you over just the a second since i mentioned chad report? all right, the center support which came out october, september? >> it came out -- >> in the microphone please. >> the first version came out almost six months ago. from reason i remember that is i finished the draft before going into achilles tendon surgery. i'm almost fully heal. we were concerned that people would be panicking and would strike a bad budget deal and wanted to emphasize that was not what, what everyone, what many, it was not a wily coyote moment

9:21 am

where the coyote goes out and goes down. just a slow, not a cliff. we still talk about cliffs now because that's what everyone is using but i try to call it a slow. spent just explain that a little bit further. so what happened on january 1 and january 2 in terms of economic impact? >> well, tax rates, tax rates go up. that means that people, tax rates go up. on employment insurance additional unemployment insurance expires. the temporary payroll tax cut expires the unemployed, long-term unemployed workers lose an average of $300 a week. people see a reduction in their take-home pay, but it's a weekly about our biweekly amount or a monthly amount but it's all the sudden you could build for the whole thing at the beginning of the. and so over time it starts to

9:22 am

build a alternative minimum tax kicks in for high income people, but that doesn't hit, if it happens commit to the actual file their returns in april. and so things started slowly, and there is plenty of time to work it out a smart response. >> bruce, on the tax side, came in at this be fixed retroactively? >> yeah, it can all be fixed retroactively. there's no constraint whatsoever. and that's one reason why i'm frankly very optimistic about this whole situation. you see, for at least four years now, the main barrier to doing any kind of sensible economic policy, especially related to dealing with the debt or the deficit has been that one of our parties is nuts. and that the republican party, they're completely out of their minds. and their attitude is, and they've torpedoed every single effort to do anything meaningful

9:23 am

about the deficit or the debt, because of one and. they adamantly refused to raise taxes by so much as a single penny. and this is what created the crisis that we are now facing. remember, the crisis all began because the republicans refused to allow the debt limit to increase. they were prepared to default on the debt. they are so obsessed with the ideology. and finally, they were brought to the bargaining table and they agreed to this sequester mechanism. and they agreed to 600 billion in cuts in defense and 600 in domestic programs. and every single republican .biz is never going to happen because what we're going to do is create this supercommittee. does everybody remember that? and they will come up with something better, everybody agrees that's a smart way to do it. but the supercommittee went completely down the drain

9:24 am

because the republicans would accept a single penny of tax increases. now, this might be a justifiable position if we were at a position where taxes were extraordinarily high. in fact, taxes have been extraordinarily low for quite a long time. the postwar average is 18.5% of gdp federal revenues. right now there are 15.8% and they have been considerably below that for the last several years. if there was one iota of truth of the republican obsession with the idea that low taxes immigrants, the economy would be booming. so basically they have zero credibility. they just lie about everything. but for some reason, the very serious people in this country take them seriously. obama does not take them over his lap and spank them as they deserve. he treats them with undue respect. but that is all change. that is all changed now, because you see, the tax increase is going to take place anyway.

9:25 am

the republicans can only stop, take some positive action to extend these tax cuts that they're so obsessed with. and by the way, republicans don't think there is from within the level spending cuts, only the tiniest little bit of tax increases what devastates the economy, contrary to everything the congressional budget office has said, which exactly the reverse. and so, that taxes will rise automatically if they don't, if they don't do anything. and they thought they were so clever two years ago, they just sat on their hands and they do anything. and, finally, at the last minute, quite predictably, barack obama caved and said, okay, okay, we will extend everything for two years and we will take up everything that i demanded that you do as a requirement. he just totally caved to the. and they congratulate themselves and patted themselves on the back, but now things are different. we've had an election. it's clear that the american people repudiated the republican

9:26 am

ideology, the exit polls showed quite clearly, 60% people support higher taxes to reduce the deficit. and so they're holding a very losing and. and what i say in my column this morning is all obama has to do issues have the courage to wade. let's wait until the taxes have actually gone up, then anything that fixes the problem is per se a tax cut, you see, relatively to the situation that will exist on january 2. so all of a sudden the political dynamics change. he has all the power, all he has to do is sit there and say, this is what i will accept. anything that you send to me that i don't want, i will simply be to end you can just start all over again. no longer would we, the fiscal cliff goes on and on and on. and republicans are absolutely guaranteed to panic. and they will be the ones who will cave if the president holds

9:27 am

to his guns, which is shown no evidence of being willing to do, for years before, but maybe now he will finally decide that he really means what he says and he is really going to do something about this. so i'm really very optimist. again think about the long-term state in my opinion this will probably be all fixed within first couple of weeks of january, made retroactive. nobody will notice it. it will have no impact on the economy whatsoever. but suppose, but we saw the problem of republican intransigence. so here's the deal. whatever's in january we make it temporary. and then we just come back and do the same thing in a few. now, people will say that's a responsible. will be facing another fiscal clip i view it as another opportunity to force the republicans to face reality on taxes. that's a very, very good, because a problem is a revenue problem primarily. if we were racing the historical share of gdp as revenues say,

9:28 am

18.5% of gdp, no one would be saying we have to do anything. we need that revenue because that provides the foundation that gives confidence to bond buyers that they will get paid the answers that they are primarily concerned -- the interest that they are primarily concerned about getting. i am very, very optimistic. might only cost about the president's willingness to negotiate getting hard with people who deserve it, hard. >> bruce, two things are possible, no more caffeine for you. [laughter] second, i think it's important given your opening remarks that would remind everybody that used to be a republican. you were what, deputy secretary for tax policy, for economic policy and the reagan treasury department. >> actually bush w. >> sorry. and you were checking and ron paul's chief economist at one time? >> yes. i drafted a tax bill as jayme will remember. spent all right, i'm a me of

9:29 am

someone who can you're cut off from caffeine, too. before you get started. can you possibly top that? >> stephanie, well, my question for you is, bringing greece into the discussion, does that do a disservice to the discussion, the scale of america and greece are so different? i do this a lot out there, and it just seems unrealistic. i believe alan sims, -- simpson, his personal issue is taxes should be increased for everyone and stay that way. are there any current significance, politicians that are actually in power now that are promoting that you? is that clear? >> well, there aren't any. so we can move on. >> stephanie, together questions because when i mentioned greece i wasn't referring to the u.s. becoming greece come in the way we often hear that we're becoming the next greece and its

9:30 am

use to create hysteria force people to start thinking about ways to reduce deficits and bring down the debt and so forth. but i was referring to is that we've seen what the impacts of austerity look like an and it would be rather foolish, knowing what we now. to go hitting implement the same sorts of policies here when the economic conditions call for something exactly the opposite, entirely different. we need pro-growth. were not going to cut our way to austerity. austerity is not the way to go. i'm hoping actually that we are going to get a chance to get the formal talks and in i can do some more. >> we have one more question. formal talks you want. you must be a professor. please. >> so since this has come up, maybe this question also is for later on, and a complete except the idea that this problem is a demand-based problem.

9:31 am

but the argument in the back of all of this is that it is a social welfare state with decent benefits like social security and medicare is simply not sustainable, that it is -- the system that has brought on the euro crisis. france, in italy, in england, and, of course, greece. >> jamie, it sounds like it's a lot for you. >> the euro crisis is the european manifestation that is a worldwide financial crisis. it's primarily a crisis of the financial system of the banking system, and the principal victims of the crisis are the peripheral countries of europe, who are severely constrained by the fact that they are part of the eurozone arrangements are and cannot finance themselves.

9:32 am

and are therefore basically subject to the big cat of the european union and the european central bank and the imf. the united states is not in that position. it's in fact exactly the opposite position. it is the country to which capital flows in a crisis, not the country from which capital retreats. the united states treasury has seen of course rising bond prices and falling interest rates on a long-term basis in the last five years. and that is a sign of two things. sort of a sign of a world situation, but it is also a sign of the fact that our institutional arrangements are such that the united states government is in good credit, is a good borrower. it is a borrower which one can have complete confidence because

9:33 am

it pays its bills in a medium that it entirely controls. that are risks to that, but they are extraordinarily remote. the risk of inflation and the risk of currency depreciation, if you consider that to be a risk. >> maybe i didn't ask the question quite right. the question is is there a robust defense of a veteran welfare state? >> in neither case is the social welfare system to be blamed. now, it is true that in europe you can't write a check if your the government of greece if you don't have money in the bank. but there is no bank, no comparable institution in the united states. united states government writes checks as required i law. it is our social welfare system such that it somehow poses a burden on the economy that cannot be sustained. no, it is exactly the opposite in fact. what happened in the crisis, and

9:34 am

it's very clear in the data, is that our system, social security, and and related programs, including the medical insurance programs, provided a massively stabilizing force. that would otherwise have deeply aggravated and accelerated the crisis. the real crisis increase right now is the cut backs in these programs, which are resulting in massive reduction in tensions, massive increases in the poverty rate. a 25% unemployment rate, and the immigration of anybody u.s. professional credential and to see a place to go, elsewhere in europe, australia and the united states, which undermines the social institutions of that country. it is the consequence of the policies that they've been ordered to follow. the united states has the option of not following those policies. and we have not followed them come in fact. we have produced a follow

9:35 am

policies which have been substantially stabilizing, with the result that we don't face the same crisis. what we are being urged to do, as i said before stampeded into doing, would, in fact, make our situation dramatically worse, not better, and we do so i think quite quickly if those policies are implemented. >> let me explain something. him the european welfare state is not too large to be managed. this is really all mythology about how europeans have big government. virtually all of the differences accounted for by one thing, instead of paying for health insurance privately, they pay through government. so just think about all the money that is taken out of your paycheck or your employer pays to pay for health insurance. we really of all that money

9:36 am

taxes, and everything else was the same, then we would have a system more like what there's this. and now we are obsessed with not having government control of health expenditures because we are afraid this will lead to higher health spending to but this is just the opposite of the truth. the truth is that every single country with national health insurance pays about half as much per help as a share of gdp as we do. we pay 17 or 18% of the entire gdp goes to health. we could have a system, health outcomes, no worse than britain, many people have visited britain, people in britain love their national health system. their mortality rates in all this other kind of stuff is no worse than ours. and we can have a huge tax cut of 8% of gdp. that's the promise of health reform. unfortunately, that argument was

9:37 am

never made back in 2009, and we still have to make it. but the point is that it's all mythology that somehow rather they have big government. we are the ones with big government. we call it the health sector. and so, and also, the real problem here in so far as with any kind of problem at all is that people, our taxes are something not high enough to pay for the spending that people absolutely insist on having. and that's fine. we have one party that has said basically are criminals, and blackmailers and they have proven they won't allow those revenues to rise. and yet they want all the same benefits they said, you know, they say we can have higher taxes because this will destroy economic growth. but back in 1993, i remember this very clearly, every single republican economist said bill clinton's tax increase was going to cause a massive recession to every single one. just like every single republican pollster said that

9:38 am

romney was going to win. they were 100% wrong, and we had a broom instead. so they have zero credibility. they are wrong about everything and they lie about everything. >> do you feel better? >> yes. [laughter] >> jamie, did you of anything else? okay. stephanie, you indicated that you have a formal think you would like to discuss, or you have some opening remarks and we will give you even though we are already open, so would you, please. you can get appear if you like, absolutely. >> i have a slight chill. -- slideshow. i thought everyone would have one. so, i guess when i started thinking about fiscal cliff and what the options are, i came up with essentially three. one is to do nothing.

9:39 am

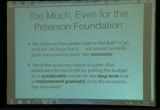

and hit the cliff and let the cuts go into place and tax increases going to place, what we've been talking about here. the other is to act with a sense of urgency, to avoid the cliff, strike some sort of a grand bargain, jump before you hit the cliff. and the last one is the one everyone here seems i think to favor, which is cannot do anything rash, to stop, take some time, and think about what you need to do to get the policy right. >> is that not working? >> i'm not sure. >> can you forward the slides? there you go. >> okay, so if we do nothing and we reached the fiscal cliff, we get pushed over the cliff, right? what does that mean? the estimates are that this means something like reduction in the 2012 budget deficit,

9:40 am

somewhere on the order of about half, not quite half, but they fall in total, a cut in the deficit of the magnitude of rent $487 billion. this is too much to even for the peterson foundation. >> go back. >> the peterson foundation said its today, it's too soon, it's coming too fast, it's too much to take all at once. it will push the economy back into recession. what we need is to go more slowly. we need that grand bargain. we need something i think with entitlements on the table because they are not on the table with the fiscal cliff, and what the peterson foundation advocates is we address the fiscal cliff by striking some kind of a deal now to avoid it am about to to put our nation on a more stable, sustainable path

9:41 am

fiscally. so far what we've heard i think from the president is him quite a willingness to go after the grand bargain. from the previously off the record that subsequently on the record interview with the "des moines register," the president says i'm absolutely confident we can get the equivalent of a grand bargain in the first six months. we can meet the bowles-simpson target, and more. i genuinely believe that the best things we can do for the economy are settle the issue of government spending entitlements and revenues so that we can provide the kind of certainty that businesses -- the business community is looking for. so what did you? most economists agree now that if we don't reach a deal and we hit the cliff, and no deal is struck after some sufficient

9:42 am

period of time, it means a recession for the u.s. economy. the business community is putting pressure on the president, and others, to come up with some way to avoid the cliff, get the deal done early. the population, as i mentioned earlier, seems eager for cooperation and compromise, a deal. so will we jump at the chance to strike the grand bargain, because it's perceived as the best way to avoid a recession, and deal with our longer-term deficit problem. these are the estimates of what would happen if we hit the cliff. first is the cdos alternative scenario where you keep the bush tax cuts and your boy the sequestration, but some other portions of what we would be facing with the cliff, in other words, extension of payroll tax, cuts goes away, unemployment

9:43 am

compensation for long-term unemployed goes away, but you keep the bush tax cuts and you avoid the sequestration, spending cuts. so if you hit the cliff, you're going into recession. gdp grows nation, turns negative and on the planet rises 9.1%. under the alternative scenario, you avoid recession. the economy continues to grow, that at the expense of rising longer-term debt. so what's the right solution? what's the right choice? there is no single magic number. but they have come up with a single magic number of sorts, and their magic number is 2 trillion. so bowles-simpson 4 trillion is today, but they argue we've already gone a good ways towards getting towards that 4 trillion, so what we need is an additional

9:44 am

$2 trillion in deficit reduction over the course of the next 10 years. that would stabilize the debt-to-gdp ratio, and put the economies long run finances in order. the goal here is to bring the deficit as a share of gdp down to around 2.5%, on average, over time. 2.5% on average over time. under bowles-simpson, the original version, i know you can't see that, but highlighted in red you see that the deficit would have gone from around 5% next year all the way down to practically zero, 10 years out. so the goal is gradual deficit reduction over time. so the deficit shrinks almost to zero at the end of the ten-year period. ..

9:45 am

>> what the center on budget and policy priorities is advocating is a $2 trillion reduction over time which would stabilize the debt to gdp ratio and put the deficit at around 2.5 president president -- 2.5% of gdp, right here. simpson-bowles aims to shrink the deficit to, essentially, zero at the end of ten years. so which of these makes sense? are any of them reasonable? i never, ever answer a question about the right size of the deficit or what the government's

9:46 am

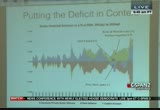

policy should be regarding the deficit without thinking of the deficit in context. i never consider it in isolation. it makes no sense to do so. understanding how the government's budget position impacts other sectors in the economy when other sectors outside the economy also matter. so in other words, we need to examine that country. and they fit together perfectly. because financial flows out of one sector go somewhere. they end up in another sector. if one sector is going to accumulate a surplus, it can

9:47 am

only be done if some other sector is running a deficit. right? that's math, as we've heard so much about, okay? this there's a reason that that graph looks like a perfect mirror image, because it is. in, on balance in net terms everything has to net to zero. so one sector's deficit is another sector's surplus. the red here, this is the public sector's budget. you can see going back as far as the 1950s that the government is almost always in the red. almost always in deficit. the private sector, which are the domestic households and domestic firms together, combined, we -- the private sector -- are almost always above zero, that is in surplus. the green is the rest of the world. and there was a time years ago when the united states ran trade

9:48 am

surpluses against the rest of the world. the rest of the world ran deficits. we had the surplus. those days are over. we now run budget -- trade deficits, and those trade deficits mean that the rest of the world is accumulating a surplus on us. so the only thing that can keep the domestic private sector in surplus is for the public sector to be in deficit. and the question is, how big does the deficit have to be in in -- to be? look what happened during the clinton years. okay, this is the last time we had surpluses in the u.s. democrats love this, right? this is the badge of honor. we were the party of fiscal responsibility, we brought you budget surpluses, and it got squandered after clinton left office and bush, you know,

9:49 am

petered away the budget surpluses. those are widely hailed as a very, very good thing. but what do they really mean? and if we're striving for balanced budgets or surpluses in the future, we better step back and figure out what that means for the domestic private sector. and what it meant was that if the government is going to collect more from us than it's going to spend -- that is, the government's going to run a surplus, and the rest of the world is going to take more from us than it's going to spend buying our goods and services -- then it drives the domestic private sector, us, into deficit. it has to. it adds up exactly. so if you've got a 4.5% trade deficit and a 1% budget surplus, the private sector's going to be in deficit 5.5%. right? the only way you keep the

9:50 am

private sector in the red, above zero, is if the government's deficit is big enough to more than offset the trade deficit. so if the u.s. is running trade deficits, current account deficits on the order of 4.5% of gdp, the government's deficit has to be at least 4.5% of gdp, or the private sector will fall below zero. every single time. okay? so here's the cbo forecast. this is what's projected to happen to the government deficit if we hit the cliff, and this is the alternative scenario. if we hit the cliff, the projection is that the government's deficit will shrink to around 2% of gdp. deficits of 2% of gdp together with trade deficits of 4.5, 4% mean the private sector is by

9:51 am

definition going to be in the negative. we'll be running deficits. here's that same image flipped over. it's how to create the mirror image of that. it just says that if the government reduces its deficit, it is reducing the surplus of the nongovernment sector. you have to be able to put these things in context. why does it matter? what difference does it make if the private sector's in surplus or deficit? turns out it makes a big difference. the private sector's budget balance is shown here in the blue line. those gray bars are recessions. we've had 11 of them since the second world war. in every single case, leading up to a recession you'll see that the private sector's budget position, its surplus, shrank. and then the private sector

9:52 am

tried to retreat. so you see them trying each time leading up to a recession. they're trying to say i don't want my surplus to get any smaller, i'm getting uncomfortable. at that point if the public sector doesn't loosen its belt as the private sector's trying to tighten its belt, we end up in a recession. okay? i just, if i leave without making any other point, the point i want to make is this very fundamental one which is that the government's deficit is equal always and everywhere to the penny to the nongovernment surplus. not just in the u.s., in every country in the world this is true. the government's deficit is the nongovernment's surplus to the penny. their red ink becomes our black ink. their deficit is our surplus. the grand bargain means austerity. those reductions this in the

9:53 am

government deficit, if the government continues to reduce its deficit, it means that the private sector's surplus will fall. and i just showed you what happens when the private sector surplus falls too far. this picture has no economic meaning. it drives lots of concern and hysteria, but it has no economic meaning. alan greenspan was asked a question by paul ryan, this was years ago. paul ryan posed the question, and he said wouldn't it be a good idea to introduce personal savings accounts? wouldn't that help put social security on a more stable, secure footing going forward? wouldn't this improve the solvency of the system? and alan greenspan gave what had to have come as quite a surprise to congressman ryan, a very

9:54 am

surprising response. he said, well, i wouldn't say that social security is on unsound footing today because there's nothing to prevent the federal government from creating all the money it wants and paying it out to someone. that's a quote. there's nothing to prevent the government from creating all the money it wants and paying it out to someone. the issue, he said, is will the real resources be there in the future for retirees when they're needed? so he turned the focus away from the financial resources, which he says can always be there, to the real resources which is what we should be focusing on, employing people, producing the capital, the goods that are going to be there for the next generation, having the real resources is what matters. it's just time that we realized that the federal government is not like a household. the u.s. dollar comes from the

9:55 am

u.s. government. it doesn't come from china. okay? we control our currency, as jamie said a moment ago. we are very, very different from the countries that adopted the euro that gave up their currencies, that can no longer issue the currency in order to spend. the united states government is not revenue constrained. that was greenspan's point. we cannot be forced into default, another point that alan greenspan has made very powerfully over and over again. there's no economic reason for a grand bargain. we are living way below our means. we're told we're living beyond our means. we're living way below our means. the red line is our potential gdp. the blue line is where we are. okay? the difference between the two is always the output and income that we sacrifice every single

9:56 am

day we fail to bring this economy back to full employment. we've got tons of spare capacity. factories aren't operating anywhere near historically high capacity utilization rates. there's all kinds of extra capacity to produce. we have millions of people who want to contribute. and we have useful things for them to do. this is our infrastructure report, right? what do we need? $2.3 trillion to bring our grade up from a d overall. important, meaningful work, people who want to work and the financial capacity to do it. and the real resources to do it. what we don't have are enough jobs. and here we sit focused on grand bargain which is another way of saying austerity. president obama got it right when he said this: companies are

9:57 am

awash with cash, and what they've been missing are enough customers out there to prompt demand and justify them spending more on plant and equipment. businesses need customers. sales create jobs. austerity is the opposite of income creating sales. it reduces income. tax increases reduce income. spending cuts reduce income. both, i would argue, are the wrong medicine for the economy today. we've seen the effects of austerity. we don't want to follow these countries over the cliff gratuitously. thank you. [applause] >> i'm going to ask chad since you're cbpp was mentioned, do you want to respond to, you know, take the next -- >> yeah. i just have a couple things to say.

9:58 am

our $2 trillion figure is not a recommendation, it's actually a response to the fact that everyone thinks that $4 trillion is what's needed to achieve -- a debt stabilization goal of stabilizing debt to gdp, to keep it rising, to keep debt from rising faster than the economy which, ultimately, is unsustainable -- how long that's unsustainable is another question and how fast it's rising is also predicting the future which is a hard thing to do as yogi berra or middle east boar, an interesting pair, said -- just to be clear what our $2 trillion says and some of the arithmetic behind it. it's not a recommendation. it says that if you want to stablize the debt the gdp ratio ten years out, you don't need four trillion which is the number that everyone thinks bowles-simpson would entail.

9:59 am

you need two trillion, and you can get one trillion of that -- and you can choose to take longer before you stabilize the debt and you stabilize at a higher level of gdp, and is you don't, you don't need as much. deficit reduction. or you can do it faster if you want to pursue the dangerous austerity program. but you get a trillion dollars just from the bush -- over ten years, just from the bush high income tax cuts. we argue very strongly that you definitely need a balanced deficit reduction program, balanced meaning revenues have to play a part, and you don't balance -- you don't stabilize the debt. we're not talking about balancing the budget, we're talking about stabilizing the debt. you don't do that on the backs of low income households. every past major budget deficit agreement we've had has been balanced, and low income programs have been exempted. the 1990 budget agreement when read my lips, george bush did

10:00 am

allow taxes to go up in 1990, there's an expansion of the earned income tax credit. '93, there was an expansion of the earned income tax credit. so we're -- when i say grand bargain, um, i'm not thinking austerity, us aer the thety, austerity. when we say grand bargain, my notion of it is when ben bernanke has said whenever he testifies, as stan said at the beginning of the conversation, accept larger budget deficits than we would otherwise have now when we have all that economic slack in the economy that stephanie's picture's shown. and defer stabilizing the debt down the road. and that -- and i don't think we have to do a lot of thinking about that. we have all the ingredients. we could do it immediately if it weren't for the political problem first identified. >> don't point at bruce when you say that. [laughter] >> before we get to your question, jamie, you've been scribbling furiously. >> three points about the long-term future.

10:01 am

the first is, as others have said, it is very difficult to forecast the fiscal position of the united states government 15 or 20 years out. the past record is atrocious. anybody who was here in the early 1990s would remember that no one then was expecting that there would be surpluses just a few years later. why did that happen? it happened because of the force and power of the information technology boom, creation of private credit and, therefore, rapid increase in tax revenues. and so what stephanie showed, this was something that was not forecast at the time. at the time those who were there in 2000 remember that the secretary of the treasury at the time was -- and the chairman of the federal reserve -- were talking about a 13-year horizon for the complete elimination of the public debt. and the congressional budget office was not forecasting that the information technology boom was an aberration that would come to an end, but it did.

10:02 am

and from 2000 forward we were back into the much more normal position of the united states government running substantial budget deficits. and as the private sector rebuilt its financial position. so that's the first point is that long-term forecasts, the idea that one can control the future position of the debt and the deficit by actions taken today is an extremely tenuous and debatable idea. second point is that there are certain assumptions being made which create extremely ostensibly scary scenarios. those numbers that show and, again, in stephanie's presentation the congressional budget office expectation that the public debt would rise close to 200% of gdp by 2035. what are they based on? two important assumptions drive these projections. one of them is that health care costs will continue to rise more rapidly than output.

10:03 am

therefore, that the share of health care in gdp will rise to some extraordinary fraction, 40% or so by, i guess, the 2080s. this is something that we know is not going the happen. it is in violation of herbert stein's famous law, stein's law which states that when a trend cannot continue, it will stop, right? the. [laughter] the reality is we're not going the spend 40% of gdp on health care. it's not going to happen. so building that into a forecast is a mistake that should be corrected. secondly, there is an assumption that interest rates will rise to levels that are consistent with perhaps what they've been in the past, but short-term interest rates if they rise more rapidly -- to levels more rapidly, higher than the rate of gdp will generate a compounding effect which will greatly increase the debt to gdp ratio.

10:04 am

but ask yourself, how likely is it that short-term interest rates are going to be driven up 400 basis points or so in three or four years? i think it's not likely at all. if it happened, the economy clearly would collapse. people's houses would lose value each more rapidity -- even more rapidly, they would default on their mortgages, you would have a disaster. not going to happen. and so adjusting these assumptions to give you a less ten den white house forecast would greatly, i think, ease the political climate surrounding this discussion. and then the third point is we need to consider particularly in light of these uncertainties what our priorities are. right now what are the problems that we can tackle? on employment, foreclosures, climate change, infrastructure. these are problems that have a

10:05 am

very concrete form and a very immediate and pressing, place very immediate and pressing demands on us. why is it that this very uncertain, very -- and in some respects highly improbable, and in any event of -- well, let's say improbable and uncertain deficit scenario is driving our short term, our immediate policy discussion? to me, it makes no sense at all. in the three or four years -- in three or four years, if it turns out that the people who have been wrong for decades on this question in spite of repeatedly asserting their position that the markets are going to turn against the u.s. government, if it turns out they're right, then the u.s. government can address that problem at that time. but there's no reason to assume it based on the record that we have so far, nor on the position that's being taken by the

10:06 am

capital markets. you do have people and institutions, banks, foreign central banks with a lot of money at play. and what is their attitude towards the united states government's fiscal position? it's very clear. look at the long-term interest rate, the 10-year, the 20-year, the bond rates on u.s. treasury bonds. they're at historic lows, and that reflects the true attitude of people who look at this with, as i say, large amounts of money on the table. >> question from the audience. yes, sir. >> yes. is this on? >> i think so, but you may have to lean down or raise the microphone to you. >> i'm basil scarlet, i lived most of my life in europe, and it always impressed me how central and northern europe, the core countries, had no difficulty financing both a welfare state and public investment. we seem to look at trade-offs here. is there, in your view, a trade-off between, between

10:07 am

growing entitlement spending -- and it is growing with the retirement of the baby boomers, the costs of medical care -- is there a trade-off between entitlement spending and more public investment? and we, i notice we don't have a separate investment budget. we seem to regard all spending, government spending as equally evil or good or doing the same thing. instead of dividing it between entitlement spending and consumption and public investment. could you comment? >> i'd say very briefly that you would see a trade-off when you see a strain on physical resources, a strain on the capacity to use capital equipment or a strain on the supply of labor. and there are no such strains. in fact, quite the contrary as

10:08 am

stephanie pointed out. we have a vast excess supply of labor, vast underutilization of capital i equipment. the one issue we need to face is resource costs and energy prices. that is not a question which is being driven by overuse at the moment, it's being driven by other factors. i'm not as optimistic as stephanie is about the long-term potential path, but is there a trade-off between what we should do to protect our elderly population and to provide adequate medical care to the whole poppation and what we should do to reconstruct our infrastructure and address energy and climate issues? no. we are underperforming on both fronts. >> but there's a -- it's not a budget tear trade-off, it's -- budgetary trade-off, as long as we think revenues can only be this high, then there's a fight among those priorities. we have to accept having higher revenues to pay for the things we want. that softens that trade-off.

10:09 am

the entitlements are not, are not a drain on real resources, they're a transfer. but there is a question of public sector investment versus what's going on in the private sector. when we're at full capacity, we have that trade-off. but the issue is, um, we think taxes should only be here, and that's -- it was probably too low leading up to now, it's certainly too low going forward. >> if i can just add one thing. your last point about capital versus operating expenses, i was a member of the president's excision to study whether the u.s. should have a capital budget, this was created during the clinton administration. i went into it thinking absolutely we should and came out of it thinking we can't only because the decisions about what will be included in the capital bum will be made by politicians -- budget will be made by politicians as opposed to accountants or someone else like that. there were also definitional questions, but think of what happened to new york in the '70s when the police department was considered a capital expense and, therefore, it was borrowed against.

10:10 am

try to imagine those same types of decisions being faced at the federal level, and suddenly education would be classified as a capital expense. it was those types of definitional questions as well as one other: what do you classify a missile as in well, it's a capital expense when you build it, it's an operating expense when you press the button. so it was getting too complicated, so i came out of it thinking you shouldn't divide it. >> and one should be very careful about arguments that hold that we should be spending more about what passes as investment and less on what's classed as, let's say, social security or what's called entitlements. for one thing, military procurement counts as investment, but we should only be doing that to the extent that we actually need it for legitimate national security purposes. and the president's point about not having as many horses and bayonets as we had in 1917 could

10:11 am

be appropriately applied to, you know, other items of equipment. and secondly, you're right, the education is, i believe, counted now as investment. and it's really hard to see why education expenditures should be counted as investment and health care expenditures accounted as a current operating cost. >> well, and you're going to get better at saying when you spend money on us, that's an investment. when seniors say just because we're older than the kids you're educating, you can invest in us as well. that's not what we're here to talk about. quick questions, please. >> my name is pat malloy. i'm a lawyer, i'm not an economist. >> pat, this is not a 12-step program. [laughter] >> but i'm delighted -- >> don't rub it in, pat, okay? [laughter] >> but i'm delighted to be here because i am interested in peace and security. stephanie, when you were putting those charts on, there were two things that i -- economists always tell me that our trade deficits are caused by the lack

10:12 am

we don't save enough. i wonder, is there causation in that formula, or is that just an economic accounting? secondly, net exports, my understanding, when you're running net exports of a major portion of your economy, a drag on economic growth for your country. so that a big part of producing economic prosperity in this country may be to go after the trade deaf set and reduce those -- deficit and reduce those as a part of our gdp growth. is that -- are my -- are these correct things to be thinking about? or is that a right analysis? >> okay. um, well, let me take the last one first. is it, is it, in fact, the case that trade deficits reduce gdp? they act as a drag on gdp? yes, it is. if the deficit were a surplus

10:13 am

instead, we would have higher gdp, presumably higher employment and higher economic growth. could we do even better, could we achieve full employment domestically with the right mix of macroeconomic policies and be able to consume everything that it's possible to produce here at home plus anything the rest of the world wants to produce and ship to us? um, i think that, that is certainly something worth thinking about. it's possible. we don't think -- we don't tend to think in those terms. we tend to think in terms of jobs leaving, corporations leaving, producing abroad whatever we buy something that's produced elsewhere, it means we didn't buy something domestically produced, and it's costing jobs. we could have a jobs program that allowed us to run our own

10:14 am

economy at full employment, take advantage of the ability to produce at capacity, have all the goods and services that we can produce domestically and, also, on top of that enjoy whatever the rest of the world wants to produce for us because right now the rest of the world, much of the rest of the world does rely on exports as part of their economic growth strategy. they want the u.s. dollar. as long as they're willing to produce and send things to us in exchange for the u.s. dollar, it could be a benefit to us if we got our own macroeconomic policy correct. >> yes, sir. >> paul gallagher, eir news service. a question for professor kelton. unfortunately, i didn't hear all of your presentation, i didn't hear everything grow proposed. but if there's no monetary debt crisis, if there's not a fiscal cliff, but a physical economic cliff, what would you, what would be your response to a

10:15 am

hamiltonian debt reorganization, creation of a national bank for purposes of pursuing infrastructure platforms and related development and assumption of such categories of death as associated with that, or congress would think buy that national bank that would have to be accompanied with a glass-teague el reform. what would you think of that way of proceeding? >> well, it's an interesting proposition. i think most of the motivation for schemes like this are driven by the belief that the debt's too big, and the way to get around that, be able to finance things, would be through direct money creation that didn't involve the offset in terms of borrowing. so, um, this is something congress could do, congress could decide that it's not going to offset dollar-for-dollar deficit spending with increased

10:16 am

borrowing, and that would, i suppose, reduce some hand wringing and anxiety about the size of the national debt. but if i think we had a better understanding of what the risks and challenges are in terms of a growing debt, and i really keep coming back to for me it's not the debt to gdp ratio that needs to be stabilized, it's the debt service that becomes an issue. it's not the debt to gdp ratio per se, but the debt service. so i just think that for me personally i think i prefer, um, a better understanding of how the monetary system actually works and understanding that the debt isn't the risk that many people make it out to be. but i don't know. jamie, do you have thoughts on the hamiltonian --? >> well, i think it comes down to the fact that the financial system on which we have relied to finance, support economic

10:17 am

growth and to set the direction of economic activity in the 1990, this was largely information technology. in the 2000s, it was housing and real estate disastrously. this financial system is not functioning as it should. and this public debt/deficit discussion distracts our attention from the fact that these central institutions that are central to the functioning of any private capitalist economy need to serve the larger public purpose of supporting economic activity and doing so in a way which is constructive to the country as a whole. and they aren't doing it. and so long as they aren't doing it, the private sector's going to be performing below par. and so long as that's the case, the public sector's going to be running substantial deficits. because the tax revenues will not be there. and so there are, i think, structural issues.

10:18 am

i think you cannot run an economy like ours on a centralized basis. youto have decentralized decisin making institution, that's what, basically, private banks are. but that until we cope with the, um, with the very substantial insol venn is si of the household, home-owning sector with the problem of private finance, we, the public sector is basically going to be playing with a very weak hand. >> um, we're going to -- we're coming close to running out of time, so i'm going to ask you the three of you, the last three questions in the audience, if you could keep your questions short and if we could keep our answers shorter, that would be much appreciated. yes, sir. >> my name's tyler healey, dr. kelton might recognize my name. >> weren't you in the fourth row, third seat? >> isn't it true that federal

10:19 am

taxes do not pay for federal spending? this question is for dr. kelton. [laughter] >> short answer. >> yes. [laughter] >> yes, sir. >> oh, okay. um, quick question. what about the kind of extranational economy? when we talk about raising revenues by taxing the rich more and everybody -- i mean, kind of the standard cynical response is that the rich will avoid paying taxes, and, um, you know, we know that people offshore money, and and also i've been reading lately about how the u.s. is also a haven for offshoring money from other, other countries. how much is that a problem in the our current situation, and how can we prevent it from being a problem in the future? >> bruce? >> well, the main problem is with corporations.

10:20 am

pulte national corporations -- multi-national corporations which are able to arrange their affairs in such a way that they don't appear to realize any profits anywhere. and so this is not just a problem for us. if you read the british newspapers, it's a huge problem over there. starbucks, apparently, has never paid any taxes in britain because it claims it's never made any profits. and there's lots of ways that these things can be done that take too much time to explain. but it's essentially a problem related to multi-national corporations. >> at those prices per cup, they don't make -- never mind. um, last question from the audience. >> my name is jean, and i'm with peace action, and i do some lobbying on the hill around military spending. and i know that you're going to be talking about that later. um, what, what i've been finding

10:21 am

is that when i talk to anybody in politics, they don't have the same understanding that you guys have about, um, the deficit and the budget. and everybody thinks that this is just a horrific problem. and so, you know, i'm trying to argue -- so i find myself in a weird position, because i've read some of scraimmy's papers, and i'm convinced this is not a problem. on the other hand, i would like to see some changes in the way that we spend our money. i think that, um, we don't need to be spending what we're spending on the military and that we could use that money in better ways. i think that, um, we could, um, require the drug company -- enable the government to, um, negotiate with the drug companies, and we could save a lot of money there. so if people are interested in the deficit, there are ways to address it, but i find myself a little bit confused about how to do the argument, and i wonder if you guys had any ideas about

10:22 am

that. >> i want to let chad, actually -- you feel like talking about that? you guys do a great job in describing these kinds of basic issues. [laughter] sorry, i didn't mean to -- >> no. well, i'm not sure exactly, i mean, there are a lot of, there seem to be a lot of parts to the question. but really how to talk about the, how to talk about the priorities sensibly and the deficit and debt sensibly, and, um, the problem is humans think that a budget is a budget and a household budget is the same as a government budget, and it's very different. there's a lot of arguments we've had, a lot of discussions we've had up here about why that's always a wrong road to go down about why they're, why they're the same. what really matters in the longer run is the productive resources in the economy and having enough, and having our priorities straight. and so arguing the priorities, arguing that -- i don't know.

10:23 am

i'm floundering because it is a big question. it's a tough question when you're confronting people that are in panic mode about the deficit. so the first thing is calm down about deficits and debt. what really matters is having a strong economy, focus on that first. and then think smart and with arithmetic and with actually knowing what's going on and with your values. >> jamie? >> very much the same message. i think we have all had the experience of being on the receiving end of a high-pressure sales job. right? where you gotta make up your mind now, and the only information you've got is the one that i'm giving you. and that, if you recognize that from a condominium sale or a car deal, i think you recognize that that's exactly what we're facing

10:24 am

as a country. in this postelection period. a high-pressure sales job based upon the extraordinarily confident assertion of things that if you may suspect if you examine them closely, you would find out were not true. and the right approach is to take a walk around the block, take a deep breath, get a cup of coffee and think things through. and i think that's what we're trying to encourage here. and there are differences of view on this possible as between finish on this panel as between some who would say, really there is this long-term deficit problem that we need to address, but we should do so in a sensible way because it's not urgent and those who say really we need to place our priorities on the immediate, concrete problems that we actually face.

10:25 am

at the very best, defer this other issue which is highly speculative to some other time when we, perhaps, have a better understanding of the facts and can make a more mature and informed decision. and i want to say i recognize that in the political climate that we've been in, it's extremely hard to find a footing for that argument. but this is a moment, really a gift from the american public to take that deep breath, to be realistic about the world as it is and to approach the next two years, four years with a kind of a new spirit of determination and realism and practicality. and i hope we can move in that direction. >> chad, 30 seconds.

10:26 am

>> at the center we do do a lot of talking to members of congress and others and persuading the public, and what you want to do is be armed with some facts and analysis. because when you get, when you start to get the hysteria, there's always the, well, actually and point to some analysis of what's really going on with social security or what's really going on with medicaid. >> um, i'm going to -- we have to end in about a minute and a half, so i want to end, i'm going to do two things. first, one quick question for everybody, same question. bring it back to the fiscal cliff. has the debate over the cliff, the fact that the defense industries and others have said this is going to cause massive layoffoffs and things, have we finally put to bed the argument that federal spending cuts don't affect jobs? can we now conclude and for at least a couple of years say that spending cuts do affect a number of people being employed? jamie? >> yes. >> stephanie? >> yes. >> bruce? >> i still don't think republicans believe it. >> defense cuts cost jobs.

10:27 am

other cuts create jobs. [laughter] >> right. >> do we feel vindicated, those of us who believe that argument? yes. but -- >> enthusiastic no. >> does the other side believe it? no. i'm with bruce. >> but we do have something that's occurred over the last several months with particularly the aerospace and defense industry saying this is going to cause massive layoffs and etc. all right, here's the last question. do you have a twitter handle or a blog you'd like to tell everybody about? jamie? >> i do not. i would simply once again recommend that you visit the web site of economists for peace and security at www.epsusa.org. >> stephanie? >> i do. my twitter handle is the opposite of the deficit hawk and the deficit dove, it's @deficitowl. [laughter] and i blog at a blog called new economic perspectives.org. >> bruce? >> i tweet tweet@brucebartlett.

10:28 am

10:34 am

10:35 am

panel on military sequestration. i'm richard coffman, i'm chairing the panel. i'm also a member of the, one of the sponsoring organizations, the economists for peace and security. our approach to the so-called fiscal cliff is, um, quite different than the panel you've just heard, and much of the -- if not almost all of the discussion -- other than the military part of sequestration. um, the fiscal cliff is considered by many with fear and

10:36 am

loathing. military sequestration, however, is seen as a possible golden opportunity to get the military house in order. or begin that process. it's argued by the pentagon leaders that the military sequester would be crippling and would endanger national security. and, of course, the aerospace industries argue that there will be tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of jobs lost if the sequester were enforced. there's another way to look at the military sequester, which is what our panel is organized to

10:37 am

do. and especially if you conclude, as do some of us, as do i, that the defense department is excessively large, riddled with inefficiency and subject to the corrupting influence of the defense industry. president obama believes that it is time to end our wars and to do nation building at home. the sequester, feared by many, could be, however, a way of opening the door to nation building. of ourselves. by shifting resources from defense to domestic needs.

10:38 am

as we saw in the disasters of katrina and sandy, our infrastructure needs alone are enormous. whether as a result of horrendous storms or not. to cite just a few, the cost of repairing and replacing our water system -- dams, levees, bridges, roads and highways -- are estimated at $100 billion just to get them in order and not to build new highway systems. our aging water systems which annually discharge billions of gallons of untreated wastewater into u.s. surface waters would cost $390 billion to replace over a 20-year period.

10:39 am

construction of seawalls which has now become a common source of discussion in the new york harbor would cost about $20 billion. many more aspects of the military sequester will be discussed by our panel, and we will begin with carl kinetta, co-director of the project on defense alternatives. >> thank you, richard. richard said that some of us are looking at the current situation as a golden opportunity. i think it might be a way that we can parse the country politically. the question where exactly does that opportunity sit, we might be looking at the military end of things and others are looking

10:40 am

at so-called entitlements. i want to begin by setting a framework for thinking about a military policy in this period. what i think it's most important for the country to recognize is that the principal strategic challenge that we face today is economic in nature, not military. that's what distinguishes this period from the years of the second world war and the cold war. our principal task from a strategic perspective is to preserve and enhance the fundamentals of national strength for the long term. and that principal my means the economy. and we need to do that in the context of a world economy that is rapidly evolving, increasingly competitive and distinctly unstable. that, i think s the framework idea, the national strategy that we need. or the national, the perspective on national strategy that we need to understand what to do,

10:41 am

um, with our military. i want to walk through some slides with you that will help frame everyone else's discussion on the panel and highlight what i think are some essential insights about our current situation with regard to defense spending. the first thing that it's important to recognize is that between 1999 and 2010 the defense department was what i call a debt and deficit leader. of -- it rose in its size faster than most other parts of the budget. it was ahead of the general rise in discretionary spending, and it rose faster than the average rise in the overall federal budget. now, there are some subsections of that budget that rose faster, but if we are looking and asking ourselves, well, who were the debt and deficit leaders during

10:42 am

this period when we moved from a balanced budget to a terribly unbalanced one, dod is among the culprits. that's evident on this chart. what you see on this chart is really a 60-year -- or it's more than that, it is a 72-year history of defense spending. the period i'm talking about is the first part of it starts right about here, and this is the high point of spending, um, and it's during that period that we accumulated a greet deal of the debt that -- a great deal of the debt that we're dealing with today. now, i'm going to return to this in a minute, but what i would like for you to do, faye, is move to the other slide. it's there somewhere.

10:43 am

>> [inaudible] >> this might be it right here. it's just a free-standing gift. okay, we don't need it. we don't need it. >> sorry. >> that's okay. the point i want to make is regardless of what you hear, it's indisputable that since 2010 there's been very little reduction in defense spending. about 5% in the real terms. so while the rest of us have been struggling hard with this question of debt and deficit reduction, there's been very little of it in the defense department. it is true that there has been a significant reduction in war spending, and that will continue. but you would expect as much. likewise, you might expect that social security spending and medicare spending, medicaid spending, that all of these things would go down and go down dramatically if people stopped dying, getting sick and getting old. but they're not -- that's not happening.

10:44 am

but with the reduction in the war and the withdrawals from the war, naturally that part of the budget has gone down. what has not gone down much at all, 5% in real terms, is what we could call the base pentagon budget. now, if we look at it from the 1999 perspective, it rose about 42 percent since then. um, so there's been a dramatic rise but very little reduction. big question sequestration poses with regard to defense, and you hear it again and again, is can we reduce defense spending by a trillion dollars over the next ten years. i think the answer to that is, yes, certainly we can. it implies rolling the budget back the 2006. it's a 13% reduction in real terms. what that really requires us to do and to do it easily is to rethink how we produce military power and how we use it in the world, what roles we want military power to fulfill. if there's an institutional

10:45 am

problem with sequestration, it's that it happens so quickly. what we can do if we are looking to make a deal is we can think about reducing defense spending 13% over three or four years which will begin the process of releasing a trillion dollars into, into the bargain that we are trying, we are trying to set. a trillion dollars over ten years is not that much. a 13% reduction over three or four years is well within the historical standard. between 1989 and 1995 the defense budget reduced by 23%. so we're talking about accomplishing significantly less than that. tomorrow the project on defense alternatives, unfortunately, i don't have it today, tomorrow we'll be releasing a report that takes us step by step toward that reduction. how might it actually be accomplished. a couple of, a couple of hints,

10:46 am